Online (art) Museum Experiences

The topic of online museum experiences (focusing again on art museums) is an expansive and complex one, growing ever wider with the creation of new digital technologies and applications. A previous posting described some of the experiences that are occurring around online collections, databases, and archives of images. It raised key issues such as how museums are partnering with broadcast media, corporations, and third-party sites such as social networking sites (SNS), how museums are navigating control (and expertise) in the midst of user-generated content and information access/excess, and also the ubiquitous debate surrounding the relationship of the virtual and the physical. This latter topic (virtual experiences) was dealt with in more detail in our last posting by Anne. Museums create online experiences based largely on three factors: 1) the emergence of new technologies; 2) their institutional priorities and goals; 3) external influences from funders, governmental entities, academia, the media, or the general public. Certainly all of these factors often overlap, such as with museums’ interest in cultivating online participation (this is dependent on new Web 2.0 technologies, museums identify this as a goal that they believe will lead to more meaningful experiences, and there are numerous studies on the importance of participatory learning both in academia and in foundations). These three factors will be woven into a discussion of many significant online art museum experiences, with noteworthy examples and their accompanying theoretical debates.

GEOSPATIAL TECHNOLOGY

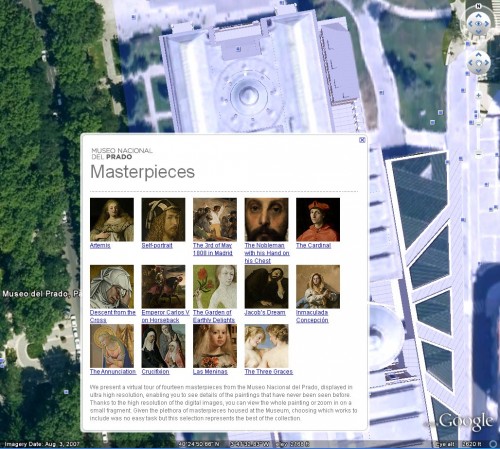

The Museo Nacional del Prado (Prado Museum) in Spain and Google Earth Spain announced their partnership in January 2009. Google Earth uses geospatial technology (also called spatial information technology) that maps features or phenomena on the surface of the earth. By downloading Google’s software for free, viewers can view 14 of the museum’s masterpieces in high definition of 14 gigapixels, along with a three-dimensional tour of the museum. This resolution is 1,400 times more detailed than any image that a common 10 megapixel digital camera could take. For all those except the privileged few scholars, these enhanced images are the closest they will ever see such masterpieces.

The 14 works featured correspond to the museum’s proposed itinerary of 15 works on their Web site as the “essential” recommended visit, highlights of their collection. The Prado’s entire collection consists of 17,300 works of art, of which only 1,300 are currently on display at the museum (an additional 3,100 are on institutional loan around the world). The museum’s Web site currently has around 2,000 images of its collection in the On-Line Gallery database, with a section called In Depth that includes detailed photographs and technical information for one highlighted work at a time. However, this project is not intended to bring together an entire collection, rather it is about specificity. Many of the original paintings are so large that, “you would need a three-meter high step-ladder” to see them up close, states Claudia Rivera of Google Spain. And that is only if you could get past the crowds and the security guards. In a Press Release (March 13, 2009), Prado director Javier Rodríguez Zapatero states that, “with the technology of Google Earth it is possible to enjoy these magnificent works as never before, allowing for details impossible to appreciate with direct contemplation.” Mr. Rodríguez even says he has used the technology to check on restoration work of the paintings. The images can be appreciated equally by scholars, students, and the general arts-interested public anywhere in the world, including those familiar with the Prado’s masterpieces and those attracted mainly by the novelty of Google Earth technology who are perhaps less familiar with the art.

It is worth mentioning that the Prado Web site has no mention of the Google Earth project on its homepage; in fact, the only place mentioned is in the Press News archive. It appears that the museum’s intent is for audiences to link to the Prado’s Web site from other popular sources such as Google, and not the other way around. This project was initiated by Google Earth Spain, and subsequently proposed to the Prado, which enthusiastically embraced it. A terrific video of the three-month process required to take 8,200 photographs of the 14 masterpieces is on YouTube.

GAMES

Games have long been offered by museums inside the galleries, usually targeting youth with old-fashioned scavenger hunts or even interactive digital games on computer kiosks. In our posting on mobile experiences, we mentioned that games are now being incorporated into cell phone audio tours as well. But with the popularization of the Internet and the development of Web 2.0 technologies that facilitate participation and collaboration, museums began to incorporate games into their Web sites, again targeting youth (also through parents and educators). Another reason for museums to engage online games is to compete with the torrent of highly visual entertainment activities now readily available such as console games, reality television, anime, virtual reality, and interactive computer games such as MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online role-playing games). Museums utilize games in the service of education. These entertainment-based learning tools – infotainment or edutainment – offer an important opportunity for learning that is social and fun, both integral to how youth experience art.

As part of the American Association of Museum’s (AAM) new Center for the Future of Museums, Jane McGonigal (Institute for the Future, Palo Alto, CA) gave a talk last year entitled Gaming the Future of Museums (the event in Washington, DC was later presented as a free webcast by the AAM). Her basic premise is that games make people happy, which is why they are so successful (as well as the fact that they provide clear instructions, feedback, and goals). She believes that museums should incorporate games because they should strive to make people happy, calling on museums to “create sustainable world-changing happiness as its primary mission.” McGonigal believes that games do all the things we need to be happy: satisfying work, the experience of being good a t something, time spent with people we like, and the chance to be a part of something bigger. She states, “We have all this pent-up knowledge in museums, all this pent-up expertise, and all these collections designed to inspire and bring people together. I think the museum community has a kind of ethical responsibility to unleash it.” Elizabeth Merritt, head of the center, believes that in the future, the best museums will be as interactive and fun as alternate reality games, both for kids and adults.

While scavenger hunts continue to be utilized for kids inside the galleries, they are also popular with adults, especially the new multimedia version that utilizes third-party sites and mobile technologies. The best example of this is the well-known Ghost of a Chance at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (July 8 – October 25, 2008), the first alternate reality game (ARG) hosted by a museum. Over 6,000 players participated online and 244 people came for the final onsite event at the museum. Multimedia platforms included Flickr, MySpace, Facebook, YouTube, the museum’s blog Eye Level, text messaging on mobile phones, as well as exploration of the physical museum. In the museum's final report and a subsequent presentation at this year’s Museum and the Web conference, Georgina Bath Goodlander (Interpretive Programs manager for the Smithsonian’s Luce Foundation Center) states that the museum was successful in achieving two of its goals: “to get people talking about our museum, to get our name out there” and “to encourage discovery.” The third goal, “to bring a new audience into the museum,” was only partially achieved. The museum did not experience many new visitors to their physical museum, but interestingly it did occur online, with increased traffic driven to their Web sites.

McGonigal states that 91% of youth under the age of 18 play games on the Internet today. Some examples of online games aimed at younger audiences include Getty Games at the J. Paul Getty Museum (Match Madness, Detail Detective, Switch, Jigsaw Puzzles), Matisse for Kids at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Waltee’s Quest: The Case of the Lost Art at the Walters Art Museum, Schoolhouse at the Yale University Art Gallery (Match Game, Art Detective), and Meet Me at Midnight at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The educational value of many of these games is not always clear, but what is clear is that kids are becoming more familiar with works of art, they are learning to look and think critically about art, and they are associating museums and art with fun.

Incorporating games – and much more – is Whyville.net, an educational virtual world for teens and pre-teens. It was launched in 1999 by Numedeon Inc. (neuroscientist Dr. James Bower while at Caltech), and now has a player base of over five million worldwide. Its Web site states that, “Whyville has its own newspaper, its own Senators, its own beach, museum, City Hall and town square, its own suburbia, and even its own economy - citizens earn "clams" by playing educational games.” In 2005, the Getty Museum became the first cultural organization to partner with Whyville, adding their arts content to the site (other museums have since joined, including the Field Museum of Chicago). In a 2005 Getty press release, Peggy Fogelman, assistant director and head of education and interpretive programs at the museum stated, “At the virtual Getty Museum, kids can explore our collections on their own terms. By making art fun and familiar, we hope that Whyvillians will venture beyond their computer monitors into art galleries and museums in their hometowns, and to the Getty Center when they visit Los Angeles. We want them to make art a part of their virtual as well as real lives.” The Getty Museum in Whyville, located in the town square, offers games such as Art Treasure Hunt, and ArtSets Gallery, and Art Hour conversations which is like a chat room for Whyvilleans. A 2006 assessment conducted by the Getty’s Susan Edwards showed some interesting results. The majority of “citizens” interviewed (ages 8 to 15) said the experience made them like art more, and they like games that challenge them. However, most said that the experience didn’t necessarily make them want to visit the physical museum more, but it did generate visits to the Getty Web site (links provided on Whyville). In general, the report stated that Whyville is a “cost-effective word-of-mouth marketing to the youth audience.”

TARGETING YOUTH

In the past fifteen or so years, teenagers (and increasingly “tweens” as well, ages 8-12) have become the center of empirical study in the US regarding learning, socializing, and digital media (as was discussed in our previous posting on library teen Web sites). A few examples include the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, the Digital Youth Project headed by Mimi Ito at UC Irvine, Harvard Professor Howard Gardner and his GoodPlay Project, the Carnegie Corporation of New York’s Council on Adolescent Development, the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media and Learning Initiative, the Milken Family Foundation’s Education Technology Project, and the Institute for Museum and Library Services’ Engaging America’s Youth initiative. Teenagers are now highly valued as representing the “pulse of contemporary culture.” Outside the academic world, teens are also the focus of market researchers and trend forecasters that depend on teenagers’ constant search for the latest product, on their free spirit of experimentation, and on their strong social networks to rapidly (virally) spread information. If the topic of teenagers, learning, and digital media has become a “fundable” one, according to the government, foundations, and influential individuals, then it will also become a priority for museums. Educational initiatives in museums have been fundable for a while, but the digital age has now shifted them onto a different plane, demanding their institutional integration.

Most museums focus on youth for their educational programming and interpretive technologies, creating social groupings (Jeremy Rifkin’s “communities of interest”) that advise the museum, produce content, and even donate money (Brooklyn Museum of Art’s 1stfans). These youth are the future generation of visitors, artists, scholars, even funders, and museums are keen to cultivate their interest and loyalty from an early age, much like brand communities in the corporate sector that foster early habits of consumption. Many museums have separate Web sites producing radio shows, zines, and podcasts managed by teen groups, and even younger kids from six years of age. In 2005, Deborah Schwartz, head of Education for the Museum of Modern Art, stated that “despite the fact that 73 percent of American youth ages 12 to 17 reportedly use the Internet, museums conduct surprisingly few media-based programs for youth.” Much has changed in four years, but these examples – extraordinary for the rich ways in which they engage youth online – are still the exception and not yet the norm.

Many museum Web sites have pages or sections dedicated to youth activities, with some museums even having their own teen councils, but this posting will focus on those that are not merely a repetition of onsite activities. The Web sites mentioned here include features that promote participation and creativity, provide options, invite the public to at least view the content (and at most to participate), and have links both back to and external to the museum. Each Web site is distinct, as are their parent museums equally distinct in their on-site teen programming, their relationship to the Web sites, and in their own histories, priorities, and organization.

The Walker Art Center is one of the most technologically experimental art museums in the country and a leader in teen programming since 1994. The Walker was the first art museum in the country to devote full-time staff to working with and building teen audiences. The teen Web site WACTAC is based on the museum’s Walker Art Center Teen Art Council (WACTAC), a group of 12 or 14 teenagers that meet weekly to design, organize, and market events and programs for other teenagers and young adults at the museum such as artist talks, exhibitions, teen art showcases, and hands-on workshops. The site is divided into four categories: Blogs, Links, Events (museum and external), and Art, although the bulk of the content and the homepage is centered on the blogs. Heideman and Siasoco (2008) note that the Walker’s first goal was to provide WACTAC with a sense of ownership of the site, with direct involvement in the process in order to ensure success. WACTAC members have a username and password that lets them post a blog and add a link, event, or artwork. They can also choose colors, set the background image and header text similar to customization options of MySpace, but they are restricted “from doing things that would severely harm the usability of the site.” It is interesting to note that this is the only site that does not allow outsiders to contribute content or participate in any online creative activities; however the public is free to read the members’ blogs and notices.

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s teen website is called youth2youth, and is designed by teens in the museum’s Youth Insights (YI) program for New York City teens. The site provides links to external resources and programs related to art, and announces YI programs at the museum that are open to other teens such as Artist and Youth: A Dialogue series, What’s Up? At the Whitney, and Teen Night Out. The Web site also features Cast a Vote, an on-line poll about art issues, The Gallery is an online exhibition space for high school age youth to submit their own artwork, and speakART is a space to share opinions and respond to other opinions on artwork in the museum. The Discussion section poses a provocative issue related to society and culture in general, and then asks a number of questions that users can respond to and view other responses. These features are all available to the public, which is an important aspect of the site, as it states that it is “a place where teens can share their insights on American art and culture with other teens around the globe.” While also open for public viewing, the section Youth Insights Reviews presents commentary on specific art-related projects, but only from program participants, and the Bulletin Board offers a space for current and past participants to post and retrieve messages (access is free and open to the public, but only with prior registration). The teens also have their own blog, which is part of the Whitney’s general blog.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)’s teen website is called Red Studio. Regarding creation and participation, Red Studio is the most interactive for all site visitors. Three activities on the homepage are “inspired by current Red Studio features and guest artists;” Remix is an interactive collage activity based on images, Fauxtogram lets you make your own virtual photographs inspired by artist Man Ray, and Chance Words allows users to create a Dadaist poem.. Unfortunately, these activities are individual ones that do not get shared with others on the site but are more like online games. Red Studio also features artist interviews by teens (currently Vito Acconci and Shahzia Sikander), along with the interactive features youDesign and Character Sketch Contest for users to participate in online activities related to creative design. The site also includes an audio program with podcasts developed by the museum’s Youth Advisory Committee (an internship for New York public school students) to “offer different perspectives on works in MoMA’s Painting and Sculpture galleries. Other features include the Talk Back bulletin board, Quick Polls, and links to museum departments as well as to external sources on artists, museums, and teen art.

WRTE RadioArte 90.5FM can be accessed through the Web site of the National Museum of Mexican Art and as a separate URL. As described on the Web site,“As the only Latino-owned, youth-driven, urban community radio station in the country, we want to encourage listeners to become involved in social justice issues and engage in dialogue through community journalism and first voice forums.” The museum acquired the license to own and operate the radio station in 1996 from the Boys and Girls Club in Chicago and they wanted to keep it a community station. As an initiative of the museum, RadioArte trains Latino youth in radio journalism and production, offering them internships and first-hand experience. The station (and the Web site) is bilingual, offering news (local, national, international), Latino music, and a community events calendar. Many of the radio shows are available on the site as podcasts, video, and “radio novelas.”

Although we are focusing on examples in the US, it is important to mention what is happening at the Tate Museum in England (encompassing Tate Britain, Modern, Liverpool, and St. Ives). Previously, the museum had incorporated a Tate Kids section within the Tate Learning page of their Web site, mostly with a few online games. In July 2008, the new Tate Kids Web site was relaunched. Tate Kids editor Sharna Jackson states, “It was hoped that the redesigned Web site would meet Tate’s mission ‘to increase public knowledge, understanding and appreciation of art’ by the creation of a colorful, relevant interactive Web site with engaging content that would both entertain and educate the intended audience of six to 12 year olds (Museums and the Web 2009). Tate Kids features a blog by kids, films, online games, Tate Create (offline activities), E-cards from the museum’s collection to send to friends, an option to change the background, My Gallery (as has been discussed in the previous post where kids can view other galleries, rate them, share theirs, and comment), and an Adult Zone for parents and educators.

Just this year, the Tate Museum launched Young Tate, “a community website by young people for young people.” Targeted at ages 13-25, Young Tate offers Exam Help, Art School (resources, links, advice), Careers at the Tate, Artists Online (blogs), RSS feed of in-gallery events, a Colour Saturation Game, and Project Gallery (podcasts, videos, and on-line projects). There is also a link to the Manifesto for a Creative Britain that was established at the Tate’s 2008 conference with a call for participation (“join the creative debate and add your own videos and images”).On-line membership is available for free, and other members can be viewed (an important consideration among this target group). Completion of a peer leadership training course at any of the Tate museums is required to be involved in the site production.

The many concrete values of these sites include instilling a sense of community and responsibility to a larger public, both the museum institution and the largely anonymous public of the Internet. This is achieved through collaboration, dialogue, and social networking both in-person and virtually, which provide the valuable skills needed for a deliberative democracy (Robert Asen, 2004). Both Asen and Robert Putnam (2000), in his well-known book Bowling Alone, talk about how citizenship engagement is necessary for democratic societies, formed through the acts of “generativity, risk, commitment, creativity, and sociability.” Pluralism is prized within a democracy, and respect for pluralist ideas, opinions, and backgrounds is generated by these sites that present various examples of “amateur” artwork, and also diverse opinions and creative choices by teenagers. Empowering youth (whom Putnam identifies as being less civic-minded) with the production of these sites, with a certain amount of control over some decisions, and with the creation of interviews, podcasts, and curating exhibitions, teaches them to become more active and involved in public acts, helping to produce a more engaged citizenry with strongly developed leadership skills. Museums also benefit by encouraging online participation that supports retention of visitors, members and funders, and attracts new ones that can sustain the organization in the long-run. The public can also provide valuable user-generated content such as personal photos and videos, scholarly assistance with online catalogs, and the creation of creative material to be publicly shared online as we have seen with the teen and kids Web sites. Online participants help museums to know their audience better, which subsequently helps better serve their community. More issues surrounding teen/youth Web sites was discussed in our earlier post focusing on libraries (Digital Media in Community Libraries, Part 2: Teen Websites).

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

The social responsibility of museums is most pertinent to their desire to serve the public and foster a sense of community. Putnam urges us to think about social capital as a public good that can be nurtured and used for the greater benefit of society. By utilizing new digital technologies with their Web sites, museums can play their part in fostering a greater sense of community with their online audiences. These new technologies allow museums to go beyond just offering information and images, and to deeply engage with their visitors, to access new ones, and to create and sustain online communities. An online community, much like any physical community, requires that individuals feels they belong to a group and understand the norms or rules of that group, that they share not only interests, but also goals, traditions and activities, that there is direct interaction and communication between individuals in the community, and that individuals contribute to the community. It is important to note that despite the creative nature of art museums, individual contribution need not be creative in nature; contributions could include sending a comment, tagging, rating an object or a tag, or blogging. Museums are creating many programs on-line that enforce a sense of collaboration and community (aside from the afore-mentioned teen/kids Web sites).

1. Wikis

The first example is based on the concept of collective intelligence or crowdsourcing: the use of wikis. According to Wikipedia, a wiki is “a collection of Web pages designed to enable anyone with access to contribute or modify content, using a simplified markup language. The collaborative encyclopedia Wikipedia is one of the best-known wikis.” Museums are using wikis to seek user-generated content, both from experts and the general public, depending on institutional goals. A few examples are the Newark Museum's wiki, and the more active Minnesota Historical Society that has two wikis (Placeography and MN150). The Michigan State University Museum has a Quilt Index, currently with 12 contributing organizations and 721 individual contributions. The challenge with these wikis, however, is that most are accessible mainly from their museum Web sites, which often have the links deeply embedded into specific sections and not as great a reach as larger SNS, media, or aggregate sites. The MuseumsWiki was started by Jonathan Bowen of London South Bank University in 2006, as a central source of information on museums, and in particular as they relate to the Internet. The Web site states that, “It is intended for museum personnel to participate in populating this wiki with museum-related material, typically in a form that is more detailed than suitable for inclusion in Wikipedia. It concentrates on technological aspects, especially museum-related wikis.” You can read more about MuseumsWiki in a paper presented by Bowen et al at Museums and the Web 2007.

2. User-generated content

A successful example of museums integrating user-generated content is the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York. Museum visitors are encouraged to upload photos they have taken at the museum to their Flickr group, the museum’s Web site will link to visitor-created videos posted on YouTube, the museum posts Visitor Video Competitions on YouTube, offers space for visitor reviews on Yelp.com, has a RSS feed on Twitter, posts podcasts on iTunesU, participates in Flickr Commons, and has an account on both Flickr and Facebook. Even more impressive is the museum’s exhibition Click! A Crowd Curated Exhibition (June 27 – August 10, 2008), organized by the museum’s manager of Information Systems, Shelley Berstein. The goal with this exhibition was to determine if James Surowiecki’s premise in his acclaimed book, The Wisdom of Crowds (2004), applied to the visual arts as well. “Is a diverse crowd just as ‘wise’ at evaluating art as the trained experts?” they ask on their Web site? The exhibition began with an open call online and onsite for artists to electronically submit photographs corresponding to the theme of “Changing Faces of Brooklyn.” The museum then opened an online forum for audience evaluation of all 389 anonymous submissions. The top 20% of the 389 images were displayed in the physical gallery, based on their relative ranking from the juried process. In total, 3,344 people participated as evaluators, providing demographic information so as to determine levels of education and art expertise. The results and statistics are fascinating and too long to list here, but are worthy of a click on their Web site to learn more. Even more fascinating is Surowiecki’s final reflections, which observe a surprising overlap between the judgment of the crowds and the experts.

3. Meetups

Museums have started to organize meetups, where online groups of people with similar interests from around the world meet offline in physical spaces. The Ontario Science Centre in Canada organized the first YouTube meetup in a museum (888torontomeetu), August 8-9, 2008, which was presented by Kevin vonAppen and colleagues at Museum and the Web 2009. The Brooklyn Museum of Art also created a new membership group called 1stfans, which is a socially networked museum group whose members are invited to exclusive social events at the museum called “1stfans meetup.” Museum Meetup is a community Web site for meetups in museums, with 51,705 members, another 38,753 interested, and 155 groups in 9 different countries.

ONLINE AND ONSITE

At this year’s Museums and the Web conference, Koven Smith from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stated that “Right now there is much more information on the Web site than inside the galleries. Our goal is to have an information-rich experience inside the gallery also.” This statement represents the concerns of many museum professionals today, that after years of trying to create an online presence reflecting the physical museum, they are now trying to take their online successes and replicate them offline. Museum consultant Nina Simon (2009, 21) concurs,

No matter how innovative your museum is on the Web, the core service of most museums is still based in the physical building. The more the online functions of a museum deviate from the onsite experience, the more your work will be seen as tangential to the mission of the institution. Now is the time to align your experiments and innovations to the core mission of your museum, and to demonstrate that your successes can be translated to the physical galleries, exhibitions, and programs.

This trend in thinking can be dangerous to the core value of museums, and in particular to art museums. Visitors at the physical museum are presented with an increasingly wide range of multimedia tools (interactive kiosks, computers, cell phone tours, audio guides, podcasts, in-gallery videos, docent tours, wall text, printed brochures and catalogues) that could potentially compete with the visual, direct art experience, especially with new media works that involve audio, video, or interactive components. In attempting to become more populist, museums provide space for alternative interpretations that are incorporated into their interpretive materials, including public figures, celebrities, and other visitors. Museums are doing great jobs of providing different channels for different visitors to explore their content, but often this causes confusion and “information overload,” especially with older visitors not accustomed to a high-tech, open-ended museum experience. In the SFMOMA study mentioned in our previous blog posting, Samis and Pau reveal that “visitors most highly value listening to the artist’s voice, followed by curators and critics, then public figures and celebrities, and lastly the voice of other visitors” (2009, 83).

Henry Jenkins talks about “transmedia storytelling” that flows across different media, and refers to the term “multiplatform entertainment” (he credits Danny Bilson), which both apply to the ways in which museums are incorporating new technologies. Steven Peltzman, MoMA’s Chief Information Officer describes this strategy. “What we want to do first is sit back and see what works and what doesn’t. Things are changing so rapidly in this world that we can’t afford to get ourselves pigeonholed into one approach” (Kennedy, 2009). Museums strive to bring their online audiences into the physical museum, using the same system of visitor categorization and replicating Web 2.0 practices and tools. But perhaps museums should also consider the alternative: that online museum experiences are entirely different than physical ones; that their online audiences are different than their physical ones; and that visitor expectations are different for the virtual and physical museum. Online experiences provide much greater benefit than just promotion and marketing of the physical museum with the goal of attracting walk-in visitors. Now with most Web hosting services offering user statistics, museums can boast impressive numbers of online audiences in addition to their physical ones. They can also generate substantial revenue online through print-on-demand services, online stores, and online payment of membership and sponsorship that could compensate for revenue earned through ticket sales.

_thumb.jpg)

At the physical space, museums can easily address crossover audiences that are accustomed to maneuvering multiple platforms by discretely placing interactive informational kiosks throughout the museum (such as the MoMA.Guide) or even a separate space within the museum (such as The Davis LAB at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, a “mix of gallery space with cyberspace”). But otherwise, there is a danger of over-stimulation, “information overload,” and uncertainty within an environment that strives to provide everyone with comfortable, uncomplicated opportunities for “education, study, and enjoyment.”

As if to preempt controversy on the subject, Prado Museum director Javier Rodríguez Zapatero stated that, “With the digital image, we’re seeing the body of the paintings with almost scientific detail. What we don’t see is the soul. The soul will always only be seen by contemplating the original.” The challenge for museums is not in choosing the best platform with which to disseminate information, or even how to make the physical museum experience more complete, but rather how to recognize the diverse types of museum experiences now available and how to best offer them to their diverse audiences.

CONCLUSION

Numerous scholars have written about the deleterious effects of anonymity and deindividuation on the Internet (Zimbardo, 1969), but newer research stresses its positive effects. The Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (Lea & Spears, 1991) is the basis for a focus on depersonalization, which alternatively seeks to explain under which conditions individuals identify more with the group than with themselves. This line of study is critical today with so many online activities that offer protection of anonymity, ostensibly encouraging participation, but potentially inhibiting collective action and the growth of online communities. Museums do not encourage anonymity on their Web sites, but rather encourage virtual and physical interactions of their audiences and members – not for the end purpose of achieving a physical museum experience, but rather to encourage participation, creation, and sharing that they believe will lead to a richer museum experience for all. Social theorist Michael Warner (2002) states that, “Reaching strangers is public discourse’s primary orientation, but to make those unknown strangers into a public it must locate them as a social entity.” Museum strangers must first be identified so they can be categorized into initial groups of interest that can then be best integrated into the larger community. The critical and challenging step to make these “unknown strangers into a public” is interactivity and discourse, primarily coming from the public, but facilitated and strategically directed by the museum through its use of new technologies.

REFERENCES

Asen, R. (2004). A discourse theory of citizenship. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 90, 189-211.

Bowen, J., et al. (2007, March). A Museums Wikii. In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/bowen/bowen.html

Cardiff, R. (2007, March). Designing a web site for young people: The challenges of appealing to a diverse and fickle audience. In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/cardiff/cardiff.html

Donath, J. (1999). Identity and deception in the virtual community. In P. Kollock & M. Smith (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge.

Goodlander, G. (2009, March). Fictional press releases and fake artifacts: How the Smithsonian American Art Museum is letting game players redefine the rules. In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/goodlander/goodlander.html

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittanti, M., boyd, d., Herr-Stephenson, B., Lange, P. G., Pascoe, C.J., & Robinson, L. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. Chicago: The MacArthur Foundation. Jackson, S. & Adamson, R., Doing it for the kids: Tate online on engaging, entertaining and (stealthily) educating six to 12-year-olds. (2009, March). In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/jackson/jackson.html

Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. New York: New York University Press. Kennedy, R. (2009, March 4). To ramp up its web site, MoMA loosens up [Electronic version]. The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2009, fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/05/arts/design/05moma.html

Pew Internet & American Life Project. (2008, April). Writing, technology and teens. Washington, DC: Author. http://pewresearch.org/pubs/808/writing-technology-and-teens

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Simon, N. (2009). Going analog: Translating virtual learnings into real institutional change. In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2009: Selected Papers from an International Conference (pp. 13-21). Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/simon/simon.html

Von Appen, K., Nicholaichuk, K., & Hager, K. (2009). WeTube: Getting physical with a virtual community at the Ontario science centre. In J. Trant & D. Bearman (Eds.), Museums and the Web 2009: Selected Papers from an International Conference (pp. 57-62). Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/vonappen/vonappen.html

Warner, M. (2002). Publics and counterpublics. Cambridge: Zone Books.