UK Student Protests: Democratic Participation, Digital Age

The stereotypical characterization of young people as politically apathetic, interested only in using digital media for socializing and gaming, has been punctured by recent events in the UK. University and high school students took to the streets to protest against the tripling of tuition fees for higher education, reductions to grants for 16-18 year olds, and cuts in government university funding. During November and December, students, staff, parents and the wider public marched in London and other UK cities and many universities had buildings occupied, with University of Kent staying in occupation over the Christmas and New Year break. Social media has been crucial in the organization of this protest movement, in reaching out to the wider public and in both engaging with and providing an alternative to mainstream media journalism. It also raises questions about the nature of democratic and civic participation in the digital age.

Organizing Resistance

The first rule of resistance is organization. Trade Unions, for example, were formed to organize workers' resistance to exploitative conditions. But the recent student movement found the National Union of Students (NUS) "bureaucratic and conservatively organised [...] with one man at the top dictating direction." Using Facebook and Twitter to organize protest marches and occupations of university buildings, and to debate the issues, allowed for much more fluid and rapid organization to emerge than would be possible going through “official” channels. It also meant that the movement could reach out beyond the university student body to include school pupils, parents, university staff and the wider public.

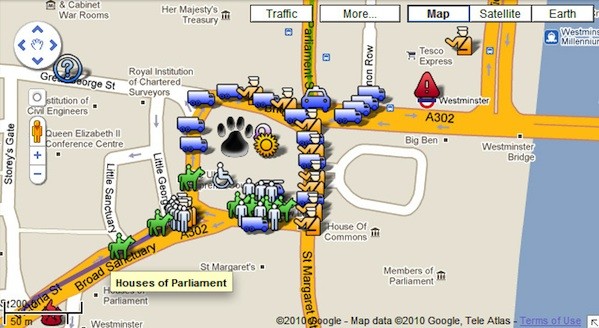

Information on protest marches and occupations was updated on a minute-by-minute basis as protesters used Twitter on their mobile phones to update their current locations and any obstacles encountered. Police attempted to “kettle” the march, corralling protesters without allowing them in or out of a contained location. Real-time updates allowed protesters to circumvent these tactics, splitting up and running around the backstreets of London like some kind of giant game of hide and seek. During the London march of Dec. 9, students occupying University College London operated a Google live map of police activity, with protesters anonymously supplying information to the occupiers, who collated and displayed it on a shared map. While police and authorities also had access to the Twitter feeds, Facebook pages and Google maps created by protesters, the speed with which protesters were able to maneuver and the distributed nature of participation meant that authorities could not effectively respond to protests via these channels.

As the occupations became hubs for the ongoing protest, this kind of distributed organization became a model for the decision-making process, with an inclusive, participatory process giving the movement a sense of legitimacy, autonomy and energy that eluded the official channels of the NUS. Rather than electing leaders and taking votes, the occupations attempted to reach consensus before briefing journalists or speaking to university management. As most occupations voluntarily dissolved after the bill to increase tuition fees was passed by parliament, the movement remains alive through these multiple, fluid and distributed networks that includes committed occupiers and interested onlookers alike.

Reaching the Public, Engaging with Mainstream Media

While the protests received extensive news coverage on TV, online and in newspapers, digital media enabled students to directly reach a much wider public, providing their own account of events and articulating the issues in their own words.

The mainstream news focused on the issue of increased tuition fees, but students’ blogs, Twitter and Facebook pages showed that their arguments were broader and more nuanced than such simple self-interest, taking in cuts across education and other public services and engaging with arguments about the economic, social and philosophical purpose of higher education. Getting these messages out to the wider public became an important part of the protesters' strategy and they called on celebrities and politicians to virally spread the word and give public messages of solidarity with the students' cause.

A disjuncture in what was considered “newsworthy” by mainstream media and what was being reported by citizen journalists involved in the protests was thrown into sharp relief late in the evening of Dec. 9.

As I continued to follow the accounts of and calls for assistance from several hundred people - some as young as 14 - being kettled on Westminster Bridge with no medical aid, toilets, food or drink, the news on my radio reported only the fact that Prince Charles' car had been attacked on his way to the theatre.

Mainstream reporting focused on the likelihood and occasional eruption of violence during the protests but the students’ own reporting showed events that were otherwise ignored, such as the group of Cambridge students who faced down police horses by singing at them, and a student activist, Jody McIntyre, who was pulled out of his wheelchair by police. This second incident was photographed by protesters and widely circulated on Twitter, and eventually picked up by the BBC, who invited him on to TV for a somewhat controversial interview.

It seems that this kind of “citizen journalism” can have an impact on the mainstream news agenda, but more importantly it also allowed the protesters’ to communicate their own, broader agenda to the wider public.

What Constitutes Democratic Participation in the Digital Age?

Some commentators have argued that “clicktivism” – online petitions, joining Facebook groups and reliance on e-marketing tactics – has undermined real political activism, giving people the feeling of being involved without actually becoming genuinely engaged in political argument or doing anything likely to bring about change.

As I followed the progress of protest marches and occupations from work and home on my computer and mobile phone, feeling virtually in amongst the action, was I in any way involved in making a difference? While there may be a real danger that digital activism can be shallow, we need to acknowledge that it may be no less “real” than taking to the streets, and may contribute substantively to political movements in a number of ways. Following the movement via digital media brings us “up close and personal” to the arguments and commitment of the protesters, and can inspire us to get more involved - whether through joining marches and protests, organizing in our own communities or writing letters to politicians and newspapers. Protesters involved in marches and occupations also appreciated the messages of solidarity they received; this kind of visible, digital support gave sustenance and encouragement to those involved in lengthy occupations that their actions were backed beyond the university. It also meant that those who were not directly involved could contribute to discussions about the issues and future direction of the movement.

Perhaps most importantly, digital activism can make an important contribution to the wider public political debate. Some critical commentators, including university management, have charged the student protesters with being unrepresentative and undemocratic by trying to effect political change through protest.

Leaving aside, for now, the issue of whether the current coalition government has a clear mandate for its political program, it is a very narrow notion that a visit to a polling booth once every four or five years constitutes democratic participation.

Democracy is an ongoing debate in which people make their voices heard in the public sphere and digital media now constitutes an important part of that public sphere. As political power is unevenly distributed in society, making audible the voices, concerns and demands of those who are overlooked is precisely what political activism is about, and protest marches, occupations and digital democratic participation are all part of the ways in which the powerless can bring their voices to a wider public debate. The spontaneous, autonomous and bottom-up nature of much of the recent student movement, facilitated to an extent by the use of digital media, perhaps allowed more genuine democratic participation than would be possible through the more formalized avenues of representative elective government or bureaucratic trade unions.

Democracy is an ongoing debate in which people make their voices heard in the public sphere and digital media now constitutes an important part of that public sphere. As political power is unevenly distributed in society, making audible the voices, concerns and demands of those who are overlooked is precisely what political activism is about, and protest marches, occupations and digital democratic participation are all part of the ways in which the powerless can bring their voices to a wider public debate. The spontaneous, autonomous and bottom-up nature of much of the recent student movement, facilitated to an extent by the use of digital media, perhaps allowed more genuine democratic participation than would be possible through the more formalized avenues of representative elective government or bureaucratic trade unions.

As students at Leeds Trinity University College re-occupy at the start of the new term, and students debate the appropriate levels and forms of organisation, decentralisation and leadership, how the movement will retain momentum remains to be seen. What we can perhaps see is the way in which many young people have become politicized, but have felt unable to make themselves heard through traditional forms of political participation. While protests and occupations have subsided, the movement lives on in both physical and virtual networks, blog discussions, email lists, Twitter feeds and Facebook groups open to participation from all, and determined to carry on making their voices heard until politicians listen.

Banner image credit: geetarchurchy http://www.flickr.com/photos/14575714@N02/5254354923/in/set-72157613228014737/

Second image credit: spyglass http://www.flickr.com/photos/31826049@N05/5204159671/

Third image credit: ucloccupation http://www.flickr.com/photos/ucloccupation/5246406333/