Wikirriculum: The Promises and Politics of an Open Source Curriculum

The idea of an “open source curriculum” has until now seemed entirely at odds with the political standardization and prescription of the curriculum. Are there any signs that curriculum will catch up with the decentered open source potential of digital media, and what are the political implications?

“Advances in technology should ... make us think about the broader school curriculum in a new way. In an open-source world, why should we accept that a curriculum is a single, static document? A statement of priorities frozen in time; a blunt instrument landing with a thunk on teachers' desks and updated only centrally and only infrequently? … We need to consider how we can take a wiki, collaborative approach to developing new curriculum materials; using technological platforms to their full advantage in creating something far more sophisticated than anything previously available.”

This statement reads like many others in the field of digital media and learning. Yet surprisingly, it was made during a speech yesterday by Michael Gove, currently the British government secretary of state for education (the most important political position in British education). The otherwise highly conservative British government, it seems, has gone smart mobbing with the crowd for its latest curriculum ideas in a post-bureaucratic age of open source, mashable policies.

The speech has wider relevance for digital media and learning. It presents a buoyant and optimistic vision of an increasingly free and autonomous curriculum environment, one where teachers will have the authority to make curriculum decisions that have been out of their hands for decades; to work creatively to produce curricula for themselves; to share materials collegiately. It draws on current examples of innovative digital media practices in schools in America, Singapore and Britain, and links together projects from MIT, Facebook, the Stanford Research Institute and the videogames industry into a political argument for educational reform.

As a practical example, as of September 2012, according to the speech, the official ICT curriculum in English schools is to be abandoned and instead “all schools will be free to use the amazing resources that already exist on the web,” while “universities, businesses and others will have the opportunity to devise new courses and exams.” The speech comes backed with a £2million investment in R&D in digital education and suggests a more creative and exciting vision for schools where learners will be able to use tools such as MIT's Scratch, utilize videogames to develop complex skills, build their own “social apps,” and make use of systems that provide personalized immediate feedback.

The School is Flat

These pronouncements seem to confirm the potential of digital media that Cathy Davidson and David Goldberg have referred to in The Future of Learning Institutions in the Digital Age as a horizontally structured and dispersed field of peer-to-peer networked learning and decentered pedagogy. Instead of a centralized curriculum that is largely defined by state textbook adoption policies and commercial publisher agreements, a flattened out networked curriculum would be deeply interwoven into the fabric of open source culture and a many-to-multitudes model of equitable intellectual exchange.

The neologism wikirriculum accurately captures the connected, hybrid nature of this kind of curriculum ideal. In the wiki ideal of creative curricular collaboration, it seems that the curriculum is being opened up to a massive process of remixing and mashing up by active and creative teachers. The implication here is that schools, and the formal educational policies which mandate what they are supposed to do, are being repositioned to look and act more like open source institutions.

In fact, Michael Gove's speech draws direct parallels between the new wiki approach to the ICT curriculum and a more devolved school reform program that is currently promoting greater autonomy for schools and a less centralized approach to educational policymaking. The argument put forward by Gove is that 21st century schooling should be aligned with the democratic structures that have been designed into the internet:

“while the technology is unpredictable and the future is unknowable, Government must not wade in from the centre to prescribe to schools exactly what they should be doing and how they should be doing it. … By its very nature, new technology is a disruptive force. It innovates, and invents; it flattens hierarchies, and encourages creativity and fresh thinking.”

Much of this is pretty simplified technological determinism, with all its talk of the “force” and “nature” of technology, but as political rhetoric it probably ought to be greeted with enthusiasm: a promising sign of a greater political openness to the curriculum making potential of digital media. As always, however, we need to be alert to some of the politics and contemporary history of such grand policy announcements.

Mash-up Empire!

Minister Gove is known in the UK for swinging fairly far over to the right of the political spectrum. The majority of his educational speeches and the policies he has signed off on have focused on the reintroduction to schools of subjects like Latin and Classics, the importance of national culture, and the history of British Empire. He represents a hard line of educational restorationism, a conservative approach to deciding what official knowledge is to be selected for inclusion in any curriculum that has prevailed in the US, too.

So what has brought about this sudden lurch into the ideals of open source, mashable curriculum creation? Has the political right begun to experience a process of wikification? What kind of politics can allow the cyberlibertarian culture of the internet to get mashed up with the conservative restorationism of colonial Empire?

Clearly, the primary influences over the direction of Michael Gove's speech are technology businesses and their interests. The speech is littered with references to the major multinationals, the software innovators of yesterday and the internet innovators of today, and it puts its emphasis on securing the skills required to create the innovations of tomorrow. Rather than stressing the cultural or civic aspects of learning through digital media, the stress is on equipping kids with the hard professional skills required for careers in computer engineering and programming. This is a familiar argument in support of a competitive high-skills, high-tech informational economy. A great deal of research now seriously questions and critiques this as a corporate fantasy that has begun to exacerbate rather than ameliorate many existing social and employment inequalities in America and elsewhere.

Perhaps even more importantly, the speech forces us to think afresh about how the knowledge that gets included in the curriculum gets selected. What knowledge? Whose knowledge? What knowledge is to be excluded? By merging the wikirriculum ideal of the curriculum into a politically right view of the importance of conservative restorationism, Michael Gove's speech invites particular kinds of voices and concerns into the debate about curriculum reform. Will we end up with some kind of politically rightist remix of the open source curriculum ideal?

As online climate change debates have demonstrated, the political right and the political left are both increasingly adept at utilizing the open source potential of the web to leverage support for their own arguments. It is certainly dangerous to presume that a kind of decentered, wiki ideal would lead to the creation of a neutral curriculum within which knowledge would be magically depoliticized. The web is awash with examples of political struggles as power and counter-power surge against one another from all possible political perspectives and mainstream and insurgent positions.

Geek Politics

Notably, too, the heroes of Gove's account—the internet entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley and Redmond—are all white, well-educated, well-off, and mostly youngish men. The inclusion of their voices in this account of the revolution in curriculum making appears to make their knowledge the legitimate source for the official knowledge of the curriculum. The kind of curriculum of Gove's political imagination is the curriculum as imagined by Gates, Zuckerman and Schmidt. As Jaron Lanier warned in an article in the NY Times, the crucial choices about what knowledge is to be passed on to young people in the digital classroom of the future are “usually not made by educators or curriculum developers but by young engineers” and the “geeks of Silicon Valley.”

The conclusion here must be that the future of the curriculum is increasingly a matter of geek politics, where school knowledge is to be defined, selected and legitimated by web entrepreneurs and computer engineers. By emphasizing the open and decentered structure of the web, they appear to suggest that official knowledge may be politically decentered too—that it will no longer be centrally prescribed according to the political viewpoints of whoever is in government. Instead, geek politics will govern and control the curriculum of the future. Which leaves us begging the question, is the curriculum of the future too important to be left to geek politics?

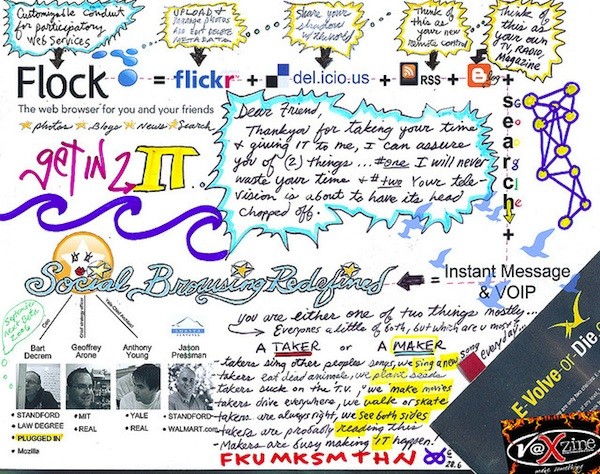

Banner image credit: vaXzine http://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/178033832/