Web Literacies: What is the 'Web' Anyway?

I’ve recently started in a new role for the Mozilla Foundation. At least half of my job there is to come up with a framework, a White Paper, around the concept of ‘web literacies’. It’s got me thinking about both parts of that term -- both the ‘web’ and the ‘literacies’. In this post I want to consider the first of these: what we mean by the ‘web’? I’ve already considered the latter in quite some detail in my doctoral thesis (available at neverendingthesis.com).

Defining the Web

Sometimes it’s important to step back from the things we take for granted and look at them in a new light. Being born in 1980, I’m in the position of both having grown up with the web in my teenage years and still being able to recall pre-web days. Even so, it’s difficult to separate out the web from the rest of my adult life. It’s increasingly interwoven with everything I do on a daily basis.

Going back to basics, the current Wikipedia definition of the web is as follows:

The World Wide Web (abbreviated as WWW or W3) commonly known as the Web or the "Information Superhighway"), is a system of interlinked hypertext documents accessed via the Internet. With a web browser, one can view web pages that may contain text, images, videos, and other multimedia, and navigate between them via hyperlinks.

So it follows that there’s at least three important aspects to the web:

1. It’s a layer on top of the internet

2. Hyperlinks are central to its structure

3. It contains artifacts (multimedia) that are embedded or otherwise available via web pages

I’ve discussed before on DML Central the importance of webmaking and avoiding the commoditization of the web. That’s not my focus in this post, but it’s certainly there in the background. The important take-away from that discussion is that the web is built upon open standards for the good of mankind. These standards are looked after by an international organization called the W3C.

Learning about How the Web Works

So if we’re talking about web literacies, then we’re talking about ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ the web in some way. The building blocks of the web are technologies built upon open standards such as HTML and CSS. Anybody can learn these ‘languages’ to build their own web pages. Fortunately, there are tools, both open source and proprietary that make this job easier. But, fundamentally, to be web literate means having at least some understanding of these building blocks of the web.

Over two billion people now use the web on a regular basis. For many people, like me, the web is a fundamental part of how they communicate -- and, therefore, how they are. We create and sustain relationships through the web. We watch videos that provoke joy, laughter, sadness, and anger. We exchange artifacts and multimedia such as photos, memes, and audio files. The web is an inherently social technology.

As Mitchell Baker, chairperson of Mozilla, put it last year: “We need open, open-source, interoperable, public-benefit, standards-based platforms for multiple layers of Internet life.” Some of this learning about openness, about standards, about things that are for the public good, some of it won’t be elegant. Some of it won’t be easy. But we at Mozilla are attempting to at least make it fun. If you haven’t seen them already there’s a plethora of Summer Code Parties where people are coming together to make, learn, hack and share.

The tools being used at these Summer Code Parties are designed to do what all educators know works -- that is, putting learning in context. Mozilla has developed three tools so far to learn about the web: Thimble, X-Ray Goggles, and Popcorn. These can all be accessed at webmaker.org. The idea isn’t to make everyone a ‘programmer’ but instead give people an insight into how the web is made and, most important of all, show them that they too can contribute to it.

Conclusion

As fellow Mozillian Gervase Markham wrote recently the web is “one of the greatest drivers of human prosperity and happiness the world has ever seen.” The web empowers people -- but only if they feel they have a stake in it. The three steps I would suggest for people to claim that stake is to first of all understand what the web is, what it does, and how people use it. Second, to learn how to both read and write the web using HTML and CSS. And, finally, to protect it; to fight for the web to remain open.

I think it’s fitting to give the last words to Tim Berners-Lee, the man credited with ‘inventing’ the web. A man who refused to patent his invention but instead ensured that it was available to everyone:

The web is more a social creation than a technical one. I designed it for a social effect — to help people work together — and not as a technical toy. The ultimate goal of the Web is to support and improve our weblike existence in the world. We clump into families, associations, and companies. We develop trust across the miles and distrust around the corner.

Amen to that.

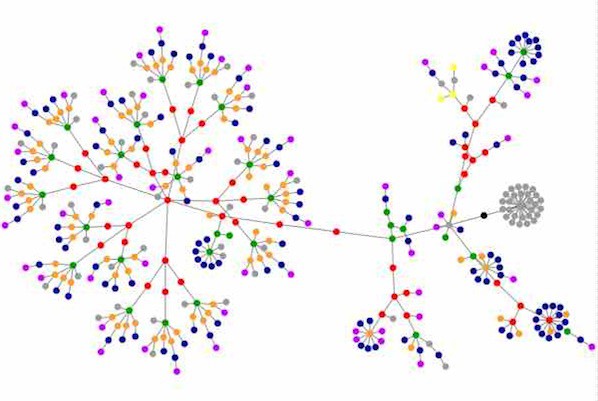

Banner image credit:saintbob http://www.flickr.com/photos/saintbob/165829023/in/photostream/